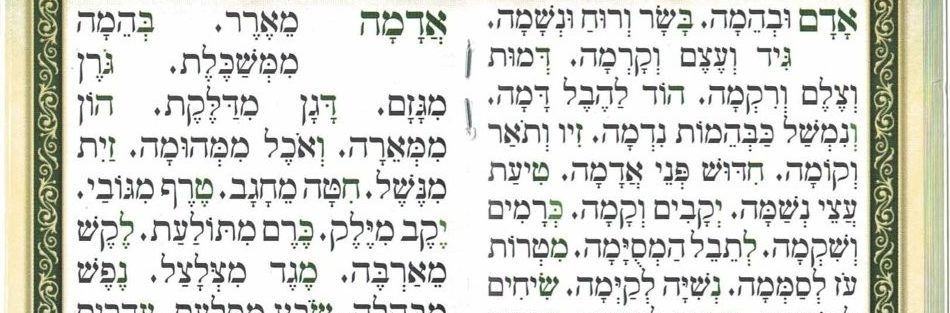

On Shabbos Chol Hamoed Sukkos, we say a special Hoshana from Rabbi Menachem ben Machir who lived about 1000 years ago. He is also the author of some of the Kinos and the ‘Reshus’ for the Chassan Torah on Simchas Torah. In the first couplet of the Hoshana we ask Hashem to forgive us and save us on Shabbos just as he saved Adam, the first man, on Shabbos. In the second couplet we ask Hashem to save us just as He saved the Jewish people in Mitzrayim by allowing us to rest on Shabbos.

The Medrash Shocher Tov (92:1) notes that when Adam ate from the Tree of knowledge he should have died. After all, Hashem had said: “on the day that you eat from the tree you will die”. Adam ate from the tree on Friday afternoon and Shabbos began before the death sentence had been carried out. The day of Shabbos stood before Hashem and complained that if Adam were to die, Shabbos would always be remembered as the day on which death came to the world. Hashem agreed and mankind was allowed to survive.

The very word Shabbos shares the root of Teshuva (repentance). Shabbos is a day on which we return to Hashem. The teshuva of Shabbos is specifically not through confessions and regrets, but rather by stopping for a moment to allow ourselves to rest. We use Shabbos to remind ourselves who we are and why we’ve been rushing all week.

One might say that Shabbos is our weekly reminder of where we are really holding. On Yom Kippur, we celebrate Shabbos Shabbason and we observe each Shabbos in an attempt to strip away the many distractions in our life and spend the day with Hashem.

A little bit later in human history Adam encountered his son Kayin who had committed the world’s first murder. When Kayin told Adam that his repentance had been accepted, Adam sang ‘Mizmor Shir L’yom Hashabbos”.

The Nesivos Shalom explains that when Kayin was given the curse of roaming the earth he complained to Hashem. How could he possibly survive the curse of ‘na v’nad tihyeh B’aretz’, that he would be homeless and wandering? How could he survive without being grounded somewhere and connected to something? In response, Hashem gave kayin an ‘os’, a sign. We usually understand the sign to be some sort of physical mark, but the Nesivos Shalom writes that the sign was Shabbos. By coming back to his roots and remaining grounded and focused every Shabbos, kayin was able to survive (see Bereishis Rabbah 22:13).

The same thing happened in Egypt. The Jewish people were losing it, we had no sense of identity and no sense of focus, but Moshe saved us by convincing Pharaoh to let them rest every seventh day. (Shemos Rabba 1:28)

I was recently talking with someone who was helping me out. I commented on how gracious he was being. The young man told me in all seriousness that he had an ulterior motive. “I try to get as many mitzvos as possible in right after Yom Kippur”, he said, “Because in my experience I won’t be doing too many good things by the time the year is over”. That is an honest, but unfortunate arrangement to have with G-d.

Imagine a Rowboat that is tied to a pier. You can row and row all day with all of your strength, but the rowboat will only go as far as the rope will allow it. We are the same way with Yom Kippur, how much can we accomplish if all of our best moments are on Yom Kippur? How long can Yom Kippur last? How far can we really grow before the holiness of Yom Kippur wears off?

This is where Shabbos comes in. By revisiting ourselves and who we have discovered ourselves to be each and every week, we can untie that rope and allow the spiritual high of Yom Kippur to stay with us and allow us to grow long after Yom Kippur is over.

0 Comments